I have noticed, as I've slowly adapted to the idea that I don't believe in god, that my dreams have changed a bit.

For some background, I'm on some medication that gives me vivid, unpleasant dreams sometimes. At first, I had nightmares every night and woke up upset and disturbed, but after a while it calmed down to what it is now: most nights I have at least one vivid dream about something I'm anxious about. This includes grades, social slip-ups, etc. I wake up sweating and nervous, but get over it almost immediately.

One interesting aspect of this side-effect is that it very clearly reveals my anxieties on an almost daily basis.

One of the major themes? Bieng outed as the godless atheist that I am.

I've dreamed about being called in to the bishop. Crap! I might lose my endorsement at BYU!

I've worried about being rejected by my brother, who is my best buddy, but who is currently Mr. SuperMissionary and comes home in 5 months.

I think my parents have even been in there, even though they have an inkling of how "misled" I am.

I don't want my professors to know, because it could affect my letters of recommendation when it comes time to apply for grad programs. I'd prefer to keep it from most of my friends, and all of my ward members (ugh, can you imagine the unwanted attention in the form of efforts to "fellowship" me?).

Maybe someday I can be more open. Definitely when I'm out of BYU my academic future will no longer ride so much on my religious beliefs. In grad school I'll probably not be expected to believe a certain thing by everyone around me. But for now it makes me a little uptight.

My mom talked about my brother-in-law Rob the other day, and warned me that I should probably avoid his blog because it "doesn't have a good spirit about it." This, of course, is Mormon for "it does not support the church wholeheartedly or reject doubt outright."

It made me want to laugh, actually. Seriously? Good thing you don't know about my blog, Mom. Rob's is pretty benign compared to mine; he's very civil and measured in his writing. I, on the other hand, rant and rave and blaspheme on a regular basis. This is where I vent when I don't want to try to argue with people.

I wonder if my parents will ever happen upon this blog. It's not impossible by any means; there are a number of ways they might find it. If they do, it might be trouble. They may have an inkling of my atheism, but they probably don't know how rabid and antagonistic toward god and religion I can be sometimes.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Blasphemous Blogging?

So none of this that I'm about to write is really very kosher by any Christian's view, I'd imagine, but if there's a hell I'm probably on the way there in any case, so I thought I'd vent a little.

What would Jesus do? We're supposed to ask ourselves that, right?

Well... based on what we know abou the guy, my guess is he'd utter a lot of platitudes, intentionally confuse people, piss off basically everybody, and then die.

But honestly, what would he do in most situations? Would he pirate MP3s? Would he drive 5 mph hour the speed limit? Would he make pizza sauce himself or buy it canned?

Basically, all I can say is, I have no friggin' clue, and as far as I can tell, neither do you.

The guy has been dead now for a couple millenia, and all we have are inconsistent accounts of dubious authorship that were written, as near as we can tell, about a century after the purported events took place.

Okay, so I know it's supposed to be "Christ lives," right? But does he really? I mean, how many people that died 2000 years ago are alive now? There are exactly zero documented cases.

In church, someone talked on Sunday about how meek and kind and forgiving and understanding Jesus is. Right? Well, except for him killing random fig trees out of spite (it was symbolic, right? Oh, wait, then why kill the poor tree instead of giving another cryptic parable about a tree?). And being really, really mean to most of the people around him. Saying downright mean and dissmissive things to his mom, family and friends. How about racism?

Like seriously. Jesus said some things that are salve for the soul or wise or cool, but he also said a bunch of inconsistent, unkind, and nonsensical things. If, that is, we trust the record at all.

So, clearly, I'm the worst blasphemer ever, but I just don't get it. I don't even know why I'd need a savior... not that I don't make mistakes, but I can't understand how god can be such a wacko that he can't figure out a way to forgive people without throwing his son out to die at the hands of "his" people. And great job, by the waty, on those people. Seems like nothing you told them made any difference, god.

Maybe there's a god. Maybe there's a Christ. Maybe I'm going to rot in hell, and all the evangelicals out there will happily dance upon my grave just before being raptured up to paradise.

But in that case, god is insane. He makes no sense at all. Have fun in heaven with your psychotic overlord.

A few days ago, the Provo Tabernacle burned to the ground. Except for the severely-damaged outside walls, the thing is just gone. But, there's a painting inside where everything except the picture of Jesus in the middle is burned.

"A Miracle!" they call it. Clearly, all pictures of Jesus are fireproof. We should just build all our houses out of pictures of him, then fire would never be a problem!

So... what I'm thinking is, if god was intent on performing a miracle that night, couldn't he have just put out the fire? It would have saved the church a bundle, Provo a lot of hassle, and would have prevented the destruction of a beautiful historic building.

Seriously, do people really believe it when they say every single slightly-good thing is a tender mercy of god, and every horrible thing is, of course, god's will? Thanks god, for the mostly-burnt painting. Maybe next you can work on saving the starving orphans of the world, or maybe the polar bears. I'd trade the damn painting for the polar bears.

I got terrible grades this semester. I'm sure some would attribute it to my utter rejection on god, recently. But you know, if prayer really worked, you'd expect the devoutly religious to have consistently higher test scores. Plently of failing students at BYU are perfect Mormons, and plently of straight-A students everywhere find the idea of a personal god laughable.

Anecdotes are not data. Your friend may have prayed and gotten her wish of a smooth day at work on the same day that many, many people prayed for a dying loved one, and the loved one died.

Game over. Thanks for playing.

What would Jesus do? We're supposed to ask ourselves that, right?

Well... based on what we know abou the guy, my guess is he'd utter a lot of platitudes, intentionally confuse people, piss off basically everybody, and then die.

But honestly, what would he do in most situations? Would he pirate MP3s? Would he drive 5 mph hour the speed limit? Would he make pizza sauce himself or buy it canned?

Basically, all I can say is, I have no friggin' clue, and as far as I can tell, neither do you.

The guy has been dead now for a couple millenia, and all we have are inconsistent accounts of dubious authorship that were written, as near as we can tell, about a century after the purported events took place.

Okay, so I know it's supposed to be "Christ lives," right? But does he really? I mean, how many people that died 2000 years ago are alive now? There are exactly zero documented cases.

In church, someone talked on Sunday about how meek and kind and forgiving and understanding Jesus is. Right? Well, except for him killing random fig trees out of spite (it was symbolic, right? Oh, wait, then why kill the poor tree instead of giving another cryptic parable about a tree?). And being really, really mean to most of the people around him. Saying downright mean and dissmissive things to his mom, family and friends. How about racism?

Like seriously. Jesus said some things that are salve for the soul or wise or cool, but he also said a bunch of inconsistent, unkind, and nonsensical things. If, that is, we trust the record at all.

So, clearly, I'm the worst blasphemer ever, but I just don't get it. I don't even know why I'd need a savior... not that I don't make mistakes, but I can't understand how god can be such a wacko that he can't figure out a way to forgive people without throwing his son out to die at the hands of "his" people. And great job, by the waty, on those people. Seems like nothing you told them made any difference, god.

Maybe there's a god. Maybe there's a Christ. Maybe I'm going to rot in hell, and all the evangelicals out there will happily dance upon my grave just before being raptured up to paradise.

But in that case, god is insane. He makes no sense at all. Have fun in heaven with your psychotic overlord.

A few days ago, the Provo Tabernacle burned to the ground. Except for the severely-damaged outside walls, the thing is just gone. But, there's a painting inside where everything except the picture of Jesus in the middle is burned.

"A Miracle!" they call it. Clearly, all pictures of Jesus are fireproof. We should just build all our houses out of pictures of him, then fire would never be a problem!

So... what I'm thinking is, if god was intent on performing a miracle that night, couldn't he have just put out the fire? It would have saved the church a bundle, Provo a lot of hassle, and would have prevented the destruction of a beautiful historic building.

Seriously, do people really believe it when they say every single slightly-good thing is a tender mercy of god, and every horrible thing is, of course, god's will? Thanks god, for the mostly-burnt painting. Maybe next you can work on saving the starving orphans of the world, or maybe the polar bears. I'd trade the damn painting for the polar bears.

I got terrible grades this semester. I'm sure some would attribute it to my utter rejection on god, recently. But you know, if prayer really worked, you'd expect the devoutly religious to have consistently higher test scores. Plently of failing students at BYU are perfect Mormons, and plently of straight-A students everywhere find the idea of a personal god laughable.

Anecdotes are not data. Your friend may have prayed and gotten her wish of a smooth day at work on the same day that many, many people prayed for a dying loved one, and the loved one died.

Game over. Thanks for playing.

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Sunday Morning Number Fun

I had an entertaining time running some (admittedly extremely rough) numbers this morning.

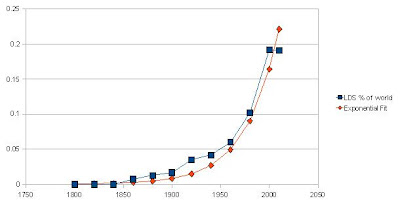

I was reflecting on how the LDS church is very proud of its exponential growth curve, and started thinking that it might be interesting to plot the percent of the world that is LDS over time, rather than the straight-up population.

Here's what I found:

So, it seems the church can still boast a nice exponential growth in terms of the portion of the world they can call their own. The fit, by the way, is (% of world)=0.001*exp(0.03*(year-1830)).

Now, a few comments before I go further. Obviously, you can't go above 100%, so this can't be a straight-up exponential, it'd have to reach an inflection point up to some point. That being said, up until about half the maximum value the church will reach, the fit should be reasonable. So we have to make some assumptions about the church's maximum size (in proportion to the world) to know how far we can set any kind of store whatsoever by this fit.

In addition, world population may reach an inflection point at any time, and further screw with our model. However, as I said, for the time being, hopefully we can trust the fit for a few years.

Finally, there is an obvious anomaly in the data right at the end where the growth rate seems to drastically drop, which might be an indication that the inflection point has already been crossed. However, for the sake of fun, I'm going to give the church the benefit of the doubt and chalk it up to noisy data.

So with that stuff out of the way, we can have a bit of fun.

One of my favorite elder's quorum discussions is "when do you brethren think the second coming will be?"

We always get the mandatory 2012 (the current favorite end-of-the-world for any crackpot theorist), and there are a lot of guesses between 10-30 years in the future. It is universally assumed that it will happen in our lifetime, or at the very latest our kids'.

I believe it is generally held in the church that a significant fraction of the world must be LDS before Jesus decides to show. I'm sure some would insist on 50% or something like that, but let's assume a smaller fraction is sufficient. Say... 10%?

Given the (idiotically optimistic) fit I've found for the church's growth rate, the church should reach 10% of the world's population at around 2130. We probably won't be around anymore. Our kids probably won't either... but maybe our grandkids. Maybe.

Anyway, like I said, the numbers pretty much explode after this, and we'd have to come up with a much better model if we want to predict any further out. In any case, if the church needs even 10% of the world before Jesus comes a-knockin, we've got a little while to wait.

Basically, the point of all this is, I can't wait for the next time someone brings this up in elder's quorum. I want to see the looks of discomfort when I tell people it seems unlikely that Jesus will be around any time in the next century, give the church's historical growth and generally-held teachings.

I was reflecting on how the LDS church is very proud of its exponential growth curve, and started thinking that it might be interesting to plot the percent of the world that is LDS over time, rather than the straight-up population.

Here's what I found:

So, it seems the church can still boast a nice exponential growth in terms of the portion of the world they can call their own. The fit, by the way, is (% of world)=0.001*exp(0.03*(year-1830)).

Now, a few comments before I go further. Obviously, you can't go above 100%, so this can't be a straight-up exponential, it'd have to reach an inflection point up to some point. That being said, up until about half the maximum value the church will reach, the fit should be reasonable. So we have to make some assumptions about the church's maximum size (in proportion to the world) to know how far we can set any kind of store whatsoever by this fit.

In addition, world population may reach an inflection point at any time, and further screw with our model. However, as I said, for the time being, hopefully we can trust the fit for a few years.

Finally, there is an obvious anomaly in the data right at the end where the growth rate seems to drastically drop, which might be an indication that the inflection point has already been crossed. However, for the sake of fun, I'm going to give the church the benefit of the doubt and chalk it up to noisy data.

So with that stuff out of the way, we can have a bit of fun.

One of my favorite elder's quorum discussions is "when do you brethren think the second coming will be?"

We always get the mandatory 2012 (the current favorite end-of-the-world for any crackpot theorist), and there are a lot of guesses between 10-30 years in the future. It is universally assumed that it will happen in our lifetime, or at the very latest our kids'.

I believe it is generally held in the church that a significant fraction of the world must be LDS before Jesus decides to show. I'm sure some would insist on 50% or something like that, but let's assume a smaller fraction is sufficient. Say... 10%?

Given the (idiotically optimistic) fit I've found for the church's growth rate, the church should reach 10% of the world's population at around 2130. We probably won't be around anymore. Our kids probably won't either... but maybe our grandkids. Maybe.

Anyway, like I said, the numbers pretty much explode after this, and we'd have to come up with a much better model if we want to predict any further out. In any case, if the church needs even 10% of the world before Jesus comes a-knockin, we've got a little while to wait.

Basically, the point of all this is, I can't wait for the next time someone brings this up in elder's quorum. I want to see the looks of discomfort when I tell people it seems unlikely that Jesus will be around any time in the next century, give the church's historical growth and generally-held teachings.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Don't Use Unfair Arguments!

I talked to my mom yesterday, and she brought up the subject of faith. She wasn't too confrontational, but definitely was trying, again, to convince me that I ought to stay active in the church.

She talked about some people she knows (disapprovingly) who have left the church, and how it was not fair to their spouses because it was understood at the beginning of the marriages that the church would be part of their marriage and family.

I don't completely object to this line of reasoning, because I've thought that maybe I should attend church socially for my wife's sake. It wouldn't be so bad, after I was out of BYU and no longer obligated to keep secret my disbelieve in god, accept callings, etc.

What I object to is the injustice of this argument when used by my mother, who very openly applauds a former Catholic minister who joined the church in her ward despite the concern that it has caused his wife. If my mom is going to use the above argument, she'd damn-well better make sure she's okay with it working against her beloved church.

The same goes for another thing she tried to tell me last night: she was telling me that religious experiences are very subtle, but that you had to learn to trust them. I indicated that some people don't really have very convincing experiences, and she said something like "but what about family and friends who have had those experiences?" I told her that that doesn't help, because there are people all over the world having religious experiences confirming the truth of vastly different worldviews. She seemed shocked and asked "what about your family and people who really care about you, though?"

I think it's only fair for her to say this if she is willing to disapprove just as strongly of people coming from other faiths into the LDS church despite their family's devotion to another faith.

She talked about another person who'd left the church because he'd tried hard and eventually given up, as if he'd done it on a whim and altogether too quickly. The idea, I believe, is that if you don't believe in the church, keep trying to until you do, or until you die. If she is willing to argue this way, she'd better be ready to accept the argument that other faiths should never convert to Mormonism, but keep plugging away trying to make their own faith work for them.

There are many other arguments of this nature thrown around all over the place. The LDS church teaches its members to avoid anything critical of the church like the plague, like it'd smut or a pack of vicious lies and authored by the devil himself. Yet the church openly and smilingly criticizes the doctrines, practices, and historical actions of other churches regularly. It's part of the missionary lessons.

Why exactly shouldn't I read anything critical about the church? Can't I make my own decisions about the validity of its claims? Getting only one narrow side of the story never seems like a good idea.

Is it thoughtcrime? Am I committing treason by even considering that the church might be based on a bunch of fiction? And yet the church and its membership are moved to tears of joy by the stories of people having doubts about their own faiths and then joining up with the LDS church when it better fit how they felt the world should operate.

If I am a traitor, then every freaking religious person who has ever joined the church is a traitor.

I understand why these arguments propagate so well in the church; they are persuasive arguments in their own ways and the church circulates ideas that are best-suited to preserve itself. It's not necessarily deliberate, it's the mind-virus adapting to its host. Among religions, blindness to your own implicit exempt status from your own arguments seems to be a particularly common symptom.

She talked about some people she knows (disapprovingly) who have left the church, and how it was not fair to their spouses because it was understood at the beginning of the marriages that the church would be part of their marriage and family.

I don't completely object to this line of reasoning, because I've thought that maybe I should attend church socially for my wife's sake. It wouldn't be so bad, after I was out of BYU and no longer obligated to keep secret my disbelieve in god, accept callings, etc.

What I object to is the injustice of this argument when used by my mother, who very openly applauds a former Catholic minister who joined the church in her ward despite the concern that it has caused his wife. If my mom is going to use the above argument, she'd damn-well better make sure she's okay with it working against her beloved church.

The same goes for another thing she tried to tell me last night: she was telling me that religious experiences are very subtle, but that you had to learn to trust them. I indicated that some people don't really have very convincing experiences, and she said something like "but what about family and friends who have had those experiences?" I told her that that doesn't help, because there are people all over the world having religious experiences confirming the truth of vastly different worldviews. She seemed shocked and asked "what about your family and people who really care about you, though?"

I think it's only fair for her to say this if she is willing to disapprove just as strongly of people coming from other faiths into the LDS church despite their family's devotion to another faith.

She talked about another person who'd left the church because he'd tried hard and eventually given up, as if he'd done it on a whim and altogether too quickly. The idea, I believe, is that if you don't believe in the church, keep trying to until you do, or until you die. If she is willing to argue this way, she'd better be ready to accept the argument that other faiths should never convert to Mormonism, but keep plugging away trying to make their own faith work for them.

There are many other arguments of this nature thrown around all over the place. The LDS church teaches its members to avoid anything critical of the church like the plague, like it'd smut or a pack of vicious lies and authored by the devil himself. Yet the church openly and smilingly criticizes the doctrines, practices, and historical actions of other churches regularly. It's part of the missionary lessons.

Why exactly shouldn't I read anything critical about the church? Can't I make my own decisions about the validity of its claims? Getting only one narrow side of the story never seems like a good idea.

Is it thoughtcrime? Am I committing treason by even considering that the church might be based on a bunch of fiction? And yet the church and its membership are moved to tears of joy by the stories of people having doubts about their own faiths and then joining up with the LDS church when it better fit how they felt the world should operate.

If I am a traitor, then every freaking religious person who has ever joined the church is a traitor.

I understand why these arguments propagate so well in the church; they are persuasive arguments in their own ways and the church circulates ideas that are best-suited to preserve itself. It's not necessarily deliberate, it's the mind-virus adapting to its host. Among religions, blindness to your own implicit exempt status from your own arguments seems to be a particularly common symptom.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Mind Virus

I believe Richard Dawkins coined this term. That makes sense, given that he is an evolutionary biologist.

The idea is something like this:

Human beings are prone to superstition, the invention of myth and legend based on over exaggeration of real past events, and unwavering belief in anything asserted by parent figures.

Humans are also pretty rational beings, so they tend to integrate all of theses myths, superstitions, and traditions into what might be called a worldview. This worldview tends to explain the origin of humanity and the world it inhabits, prescribe proper behavior of individuals toward one-another (as well as toward the ubiquitous imagined anthropomorphic forces controlling the world), and address the terrifying concept of the inevitability of death.

However, despite the human tendencies mentioned above, these worldviews and their constituent parts are not invulnerable. Humans are clever, and very good at pattern-recognition. When the patterns of the worldview become inconsistent with the observed patterns in the world, humans will often reject all or part of the worldview. For example, do you believe that spilling salt is bad luck, or saying "Bloody Mary" repeatedly in a darkened room with a mirror will bring forth some unholy being to torment you? If not, why don't you?

When a young child, I tested the Bloody Mary one. My friends insisted it was true, but I was skeptical. However, I was terrified, because I'm human and I tend to accept these superstitions naturally, on some level. Still, I was not afraid enough that I did not go into the bathroom (half-petrified) and test it thoroughly. Once experience had failed to confirm the purported truth of Bloody Mary, I came to assume the falsehood of this particular myth.

The idea of a mind-virus is that these ideas, these myths and superstitions, are passed from person to person easy. However, the human mind has defenses against false ideas (skepticism, rational approach to reality). The ideas resilient to these defenses tend not to be widely abandoned, but passed on further. The ideas mutate and grow over time, and the mutations most favorable to the survival of the idea are passed on, where the other ones are quickly abandoned. This, as I'm sure you've seen, is the source of the term "mind-virus," and I find that the behavior of these ideas are actually very analogous to the evolution of an actual contagious virus.

After all, a virus is just RNA in a protein shell, and is little more than information. This is hauntingly close to what an idea consists of. Virii do not reproduce like cellular organisms, they simply deliver the information, which has evolved through selection to hijack existing cells for the reproduction and distribution of the virus.

So, I have been musing over the potential dangers to a mind-virus posed by a human being, and the possible defenses the virus might evolve.

Human Defense:

Experimental refutation of an idea. The mind, as I said, can go out and test ideas, and will usually abandon them when they have been thoroughly tested without significant matching results.

Viral Reactions:

-If the idea cannot be tested, it cannot be experimentally disproved.

-If the idea includes anecdotal accounts of strong evidence for its veracity, it may weaken refutation by apparent (but unverified) counterexample.

-If the idea is tied strongly to another idea which is accepted, the accepted idea can anchor the attached idea by way of the unwillingness to accept the falsehood of the accepted idea (which in many cases would indeed be shown to be false if the connected idea were disproved.)

Human Defense:

Rational inconsistency of parts of an idea or worldview. Human beings are adept at finding the incongruities of two or more assertions, and will often abandon at least one idea in order to escape from the illogic.

Viral Reactions:

-If an appeal to cognitive dissonance is packaged with the idea, a person might well rationalize away or ignore the obvious inconsistencies. Often this takes the form of "At least do/try it for's sake."

-If an appeal to human ignorance is made, a person might accept inconsistent assertions, pending further data. This is actually the virus commandeering the person's skepticism; it is very true that knowledge gained later might clarify the apparent inconsistency. A strengthening factor often included is a hint or assertion that such knowledge is had somewhere, and may well be on its way.

Human Defense:

Experience and a realistic world-view. Human begin to expect the world to act as observed once they have gained enough experience. Skepticism is the natural reaction to claims inconsistent with that pattern.

Viral Reactions:

-If the virus comes packaged with some rationalization that seems logical, the inconsistency can be made to seem trivial. Jonathan Swift's satirical A Modest Proposal is an demonstration of how preposterous ideas can be cast in a light making them seem perfectly reasonable.

-If a virus appeals to deep-seating anxieties common to human beings, the strong desire to escape to safety from these anxieties might cause a person to strongly accept an idea immediately, making skeptical investigation less likely. Unemployment, disease, death, loneliness, etc, can cause people to go so far as to buy spring water from Tibet and to vote for sketchy candidates making sweeping promises.

Human Defense:

An understanding of uncertainty, probability, and statistics. This is related to the experienced, realistic world-view, but is more rational than intuitive. The unlikelihood of the truth of an assertion compared to alternatives is extremely damaging to an idea. If you flip a coin and heads comes up twice, there is little reason to assume a biased coin. If you flip a coin 1000 times in a row and get heads, to suspect the coin is the logical reaction. It is not that the alternative is impossible, but it is much less likely.

Viral Reaction:

-If an idea comes with an argument containing bad math or unverified statistics, it still creates some apparent credibility of the idea. "Most Americans prefer green" is far less believable than "60% of Americans prefer green," because the quantitative assumption seems authoritative and precise.

Now, I ask, what types of worldviews and ideas are most resilient? Things that turn out correct, for one thing. But also, religions (the ones that last) tend to have almost every beneficial mind-virus characteristic, and so they become prolific and resilient.

Religions make claims on subjects that cannot or cannot yet be experimentally examined.

-eg The existence of god.

Religions perpetuate unverifiable anecdotes.

-eg The resurrection of Jesus.

Religions tie ideas together firmly to anchor less-secure ideas.

-eg If you have faith, you can believe.

Religions tend to make appeals to emotions in order to promote cognitive dissonance.

-eg Just try it for a while, for (family member)'s sake.

Religion regularly implies higher intelligence and a grand scheme beyond human comprehension.

-eg We cannot understand (inconsistent doctrine) in this life, but all will be made clear in heaven.

Religions employ flowery rhetoric which seems sound, but actually contains assumptions and fallacies.

-eg All things have a beginning, so nothing could exist unless there was something (god) to start it.Religions constantly appeal to almost-universal human anxieties.

-eg Answers addressing "Where did I come from, why am I here, where am I going?"

Religions quote false or unverified statistics and use bad math constantly.

-eg The watchmaker argument.

You'll notice that these are in the same order as the bullet points I listed above enumerating the various viral survival mechanisms. Religion nearly universally contains many, many, of each of these mechanisms.

But this makes sense: religions only survive when they are resilient to skepticism and disproof. Religion has existed most likely since the dawn of human culture, and has evolved over the millennia to be what it is now: very well-suited to the human mind. Modern religion is a nearly perfect mind-virus.

Any person will agree, I think, that most religions make many false claims (because clearly not many more than one can possibly be correct). The fact that these religions remain prolific, and their followers faithful, indicates the human vulnerability to viral (and sometimes virulent) ideas.

The idea is something like this:

Human beings are prone to superstition, the invention of myth and legend based on over exaggeration of real past events, and unwavering belief in anything asserted by parent figures.

Humans are also pretty rational beings, so they tend to integrate all of theses myths, superstitions, and traditions into what might be called a worldview. This worldview tends to explain the origin of humanity and the world it inhabits, prescribe proper behavior of individuals toward one-another (as well as toward the ubiquitous imagined anthropomorphic forces controlling the world), and address the terrifying concept of the inevitability of death.

However, despite the human tendencies mentioned above, these worldviews and their constituent parts are not invulnerable. Humans are clever, and very good at pattern-recognition. When the patterns of the worldview become inconsistent with the observed patterns in the world, humans will often reject all or part of the worldview. For example, do you believe that spilling salt is bad luck, or saying "Bloody Mary" repeatedly in a darkened room with a mirror will bring forth some unholy being to torment you? If not, why don't you?

When a young child, I tested the Bloody Mary one. My friends insisted it was true, but I was skeptical. However, I was terrified, because I'm human and I tend to accept these superstitions naturally, on some level. Still, I was not afraid enough that I did not go into the bathroom (half-petrified) and test it thoroughly. Once experience had failed to confirm the purported truth of Bloody Mary, I came to assume the falsehood of this particular myth.

The idea of a mind-virus is that these ideas, these myths and superstitions, are passed from person to person easy. However, the human mind has defenses against false ideas (skepticism, rational approach to reality). The ideas resilient to these defenses tend not to be widely abandoned, but passed on further. The ideas mutate and grow over time, and the mutations most favorable to the survival of the idea are passed on, where the other ones are quickly abandoned. This, as I'm sure you've seen, is the source of the term "mind-virus," and I find that the behavior of these ideas are actually very analogous to the evolution of an actual contagious virus.

After all, a virus is just RNA in a protein shell, and is little more than information. This is hauntingly close to what an idea consists of. Virii do not reproduce like cellular organisms, they simply deliver the information, which has evolved through selection to hijack existing cells for the reproduction and distribution of the virus.

So, I have been musing over the potential dangers to a mind-virus posed by a human being, and the possible defenses the virus might evolve.

Human Defense:

Experimental refutation of an idea. The mind, as I said, can go out and test ideas, and will usually abandon them when they have been thoroughly tested without significant matching results.

Viral Reactions:

-If the idea cannot be tested, it cannot be experimentally disproved.

-If the idea includes anecdotal accounts of strong evidence for its veracity, it may weaken refutation by apparent (but unverified) counterexample.

-If the idea is tied strongly to another idea which is accepted, the accepted idea can anchor the attached idea by way of the unwillingness to accept the falsehood of the accepted idea (which in many cases would indeed be shown to be false if the connected idea were disproved.)

Human Defense:

Rational inconsistency of parts of an idea or worldview. Human beings are adept at finding the incongruities of two or more assertions, and will often abandon at least one idea in order to escape from the illogic.

Viral Reactions:

-If an appeal to cognitive dissonance is packaged with the idea, a person might well rationalize away or ignore the obvious inconsistencies. Often this takes the form of "At least do/try it for

-If an appeal to human ignorance is made, a person might accept inconsistent assertions, pending further data. This is actually the virus commandeering the person's skepticism; it is very true that knowledge gained later might clarify the apparent inconsistency. A strengthening factor often included is a hint or assertion that such knowledge is had somewhere, and may well be on its way.

Human Defense:

Experience and a realistic world-view. Human begin to expect the world to act as observed once they have gained enough experience. Skepticism is the natural reaction to claims inconsistent with that pattern.

Viral Reactions:

-If the virus comes packaged with some rationalization that seems logical, the inconsistency can be made to seem trivial. Jonathan Swift's satirical A Modest Proposal is an demonstration of how preposterous ideas can be cast in a light making them seem perfectly reasonable.

-If a virus appeals to deep-seating anxieties common to human beings, the strong desire to escape to safety from these anxieties might cause a person to strongly accept an idea immediately, making skeptical investigation less likely. Unemployment, disease, death, loneliness, etc, can cause people to go so far as to buy spring water from Tibet and to vote for sketchy candidates making sweeping promises.

Human Defense:

An understanding of uncertainty, probability, and statistics. This is related to the experienced, realistic world-view, but is more rational than intuitive. The unlikelihood of the truth of an assertion compared to alternatives is extremely damaging to an idea. If you flip a coin and heads comes up twice, there is little reason to assume a biased coin. If you flip a coin 1000 times in a row and get heads, to suspect the coin is the logical reaction. It is not that the alternative is impossible, but it is much less likely.

Viral Reaction:

-If an idea comes with an argument containing bad math or unverified statistics, it still creates some apparent credibility of the idea. "Most Americans prefer green" is far less believable than "60% of Americans prefer green," because the quantitative assumption seems authoritative and precise.

Now, I ask, what types of worldviews and ideas are most resilient? Things that turn out correct, for one thing. But also, religions (the ones that last) tend to have almost every beneficial mind-virus characteristic, and so they become prolific and resilient.

Religions make claims on subjects that cannot or cannot yet be experimentally examined.

-eg The existence of god.

Religions perpetuate unverifiable anecdotes.

-eg The resurrection of Jesus.

Religions tie ideas together firmly to anchor less-secure ideas.

-eg If you have faith, you can believe.

Religions tend to make appeals to emotions in order to promote cognitive dissonance.

-eg Just try it for a while, for (family member)'s sake.

Religion regularly implies higher intelligence and a grand scheme beyond human comprehension.

-eg We cannot understand (inconsistent doctrine) in this life, but all will be made clear in heaven.

Religions employ flowery rhetoric which seems sound, but actually contains assumptions and fallacies.

-eg All things have a beginning, so nothing could exist unless there was something (god) to start it.Religions constantly appeal to almost-universal human anxieties.

-eg Answers addressing "Where did I come from, why am I here, where am I going?"

Religions quote false or unverified statistics and use bad math constantly.

-eg The watchmaker argument.

You'll notice that these are in the same order as the bullet points I listed above enumerating the various viral survival mechanisms. Religion nearly universally contains many, many, of each of these mechanisms.

But this makes sense: religions only survive when they are resilient to skepticism and disproof. Religion has existed most likely since the dawn of human culture, and has evolved over the millennia to be what it is now: very well-suited to the human mind. Modern religion is a nearly perfect mind-virus.

Any person will agree, I think, that most religions make many false claims (because clearly not many more than one can possibly be correct). The fact that these religions remain prolific, and their followers faithful, indicates the human vulnerability to viral (and sometimes virulent) ideas.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

God's Appendix

Man is supposed to be created in god's image, right?

In Mormon theology, this is interpreted quite literally as meaning that god has a body, normal human size, male, just "exalted." Exalted means that it is immortal and has no blood for some reason? But in every way it is supposed to be analogous to our bodies, just without blemish or fallibility.

I am aware that in other Christian traditions, this bit of doctrine is interpreted much more loosely... god is somehow ehtereal and everywhere at once, so he doesn't have a body per se, but he's like us in some sense. I guess we can regard god as fundamentally human, in this case, except "higher" in some way.

I was just thinking about what the implications of this idea, that god is like a man, are. I was of course thinking in the Mormon context because that's how I grew up, so I was imagining a physical god with a body like a human's.

It occured to me: does god have an appendix? How about tonsils? Adenoids? How about all of our junk DNA, most of which has absolutely no effect in our makeup and development? If so, why does god have useless organs and parts? He can hardly be called "perfect" in that case.

How about pores? Does god sweat? Can he sneeze? Does he have to clear his divine ears of heavenly earwax? It all seems like a pretty funny way to think of deity.

But for that matter, if god can get things done just by speaking or willing, why does he even need arms and legs and fingers, and in short, a physical body at all?

If we take the tack that god is not physical, but sort of an incorporeal-but-human being, we come up with some additional concerns: Exactly how is man in god's image?

I can think of several possibilities, of course. Our minds, our moral intuition, our imaginations, etc, are all modeled after god's. We are sentient, modeled after god's sentience.

This is fine as a concept. However, it collides with some other doctrines that I've considered:

For example, that "God's ways are not our ways." I've been told this over and over when I have been questioning god's actions, given the world as it is. Don't try to justify god, his thoughts and ways are so much higher than ours that we can't hope to ever follow them.

I can understand where this is coming from, but it seems inconsistent with the above-mentioned doctrine. If we are made in god's image but he is not physical, how are his ways not our ways? Our behaviors are presumably based on his ways. Maybe it is that we are like children, not quite up to his level of abstraction. But I really wonder how; adult human beings are capable of extremely high levels of abstraction. Non-euclidian geometries, for example, represent a very thouroughly-studied field that is purely abstract; it has absolutely no relation to our experiences except the very exceptional case of the geometry which is the one of our experience. If it is imaginable, we can think about it and study it. If we can't make any headway in metaphysics, it is logically impossible as Kant demonstrated. If god has tools we do not, then he is not necessarily more capable than we are, any more than a physics student today is more capable than Isaac Newton. Just lucky.

So, if god has no body and does not think anything like us, in what way exactly are we made in god's image?

Is it not more likely that god is made in our image?

He sure tends to conform to the prevailing philosophy of a given people at a given time, but only in that time to those people.

In Mormon theology, this is interpreted quite literally as meaning that god has a body, normal human size, male, just "exalted." Exalted means that it is immortal and has no blood for some reason? But in every way it is supposed to be analogous to our bodies, just without blemish or fallibility.

I am aware that in other Christian traditions, this bit of doctrine is interpreted much more loosely... god is somehow ehtereal and everywhere at once, so he doesn't have a body per se, but he's like us in some sense. I guess we can regard god as fundamentally human, in this case, except "higher" in some way.

I was just thinking about what the implications of this idea, that god is like a man, are. I was of course thinking in the Mormon context because that's how I grew up, so I was imagining a physical god with a body like a human's.

It occured to me: does god have an appendix? How about tonsils? Adenoids? How about all of our junk DNA, most of which has absolutely no effect in our makeup and development? If so, why does god have useless organs and parts? He can hardly be called "perfect" in that case.

How about pores? Does god sweat? Can he sneeze? Does he have to clear his divine ears of heavenly earwax? It all seems like a pretty funny way to think of deity.

But for that matter, if god can get things done just by speaking or willing, why does he even need arms and legs and fingers, and in short, a physical body at all?

If we take the tack that god is not physical, but sort of an incorporeal-but-human being, we come up with some additional concerns: Exactly how is man in god's image?

I can think of several possibilities, of course. Our minds, our moral intuition, our imaginations, etc, are all modeled after god's. We are sentient, modeled after god's sentience.

This is fine as a concept. However, it collides with some other doctrines that I've considered:

For example, that "God's ways are not our ways." I've been told this over and over when I have been questioning god's actions, given the world as it is. Don't try to justify god, his thoughts and ways are so much higher than ours that we can't hope to ever follow them.

I can understand where this is coming from, but it seems inconsistent with the above-mentioned doctrine. If we are made in god's image but he is not physical, how are his ways not our ways? Our behaviors are presumably based on his ways. Maybe it is that we are like children, not quite up to his level of abstraction. But I really wonder how; adult human beings are capable of extremely high levels of abstraction. Non-euclidian geometries, for example, represent a very thouroughly-studied field that is purely abstract; it has absolutely no relation to our experiences except the very exceptional case of the geometry which is the one of our experience. If it is imaginable, we can think about it and study it. If we can't make any headway in metaphysics, it is logically impossible as Kant demonstrated. If god has tools we do not, then he is not necessarily more capable than we are, any more than a physics student today is more capable than Isaac Newton. Just lucky.

So, if god has no body and does not think anything like us, in what way exactly are we made in god's image?

Is it not more likely that god is made in our image?

He sure tends to conform to the prevailing philosophy of a given people at a given time, but only in that time to those people.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

I wish I could believe in god

It would be great if the truth-claims of religion were true. It would be awesome if the LDS church were true, the promised results from living a faithful life are pretty darn good.

But I just can't believe god exists. At least not the god I've been taught about. The world is not like the world that religions say it is. It is not like the world one would expect to have been created by a powerful, benevolent being. The evidence seems completely contrary. For every person god supposedly helps, dozens of people are left to die by way of disease, violence, starvation, and other unimaginably terrible deaths.

I have been told over and over that god allows evil in the world for free will's sake. However, this explanation seems weak to me. If god is so powerful, he might come up with some other way. I don't think the "best of all possible worlds," as Leibniz concluded the world must be if created by a benevolent god, is one where the prayers of a kid looking for his teddy bear or a woman for her car to start so she can make it to work are answered even as innocent children burn or starve to death elsewhere. If god exists and is well-meaning, he really, really needs to rethink his priorities.

I've read many times that it takes more faith to be atheist than theist. While I admit that someone who believes that there is no god and could never be convinced otherwise is probably dogmatically clinging to faith of a kind, I don't think that that's how it is for me. Presented with the right evidence, I would believe in god. But it seems more likely than not that there is no personal god, to me, because the world I find myself in is inconsistent with that idea. So how am I clinging to faith more than a theist, if I interpret things in the most realistic way possible while being prepared to change my beliefs based on new data?

I'm sure there are those who would accuse me of not giving god a chance. This is bull. I served a full-time mission working every waking hour, seven days a week, for two years. I rode a bike through the hail and in 110 degree 90% humidity, being rejected from dawn to dusk in a language I had to learn as I went. I have always given 1/10 of my income to the church. I have spent my life saying constant daily prayers, reading the scriptures, participating in church service, and forever ignoring any doubts that came my way.

I would say that 20+ years seems long enough. If god were going to throw me a bone, I'd think maybe he would have done it by this time. After all, I've probably lived more than a quarter of my life, and some of my most important decision-making years at that, in his service.

Even if there turned out to be a god who was even slightly interested in human affairs and the lives of individuals, I very much doubt that I was raised in his correct religion. What are the odds? Not good. Ignoring the church's inconsistencies in teachings throughout the last couple of centuries, it occurs to me that maybe god would do a better job promoting the church that he supposedly endorses.

Maybe there is some kind of "first cause" or "creator" of the universe, but there is nothing to indicate this thing's characteristics. Even its sentience is a completely baseless assumption. This "god" could very well regard the universe as a toy, maybe it hasn't even noticed humanity in all of the vastness of space. Or maybe it has, is malevolent, and brings suffering into the world for its own pleasure. So the entire basis of a rational path to theism is groundless... if you have been personally convinced of god's existence, fine, but you can't use that to convince me, your conversion experience is not even consistent with the conversions of others!

Now I'm ranting, so I'd better stop. But people say some dumb things about the way I think, and sometimes it irks me.

But I just can't believe god exists. At least not the god I've been taught about. The world is not like the world that religions say it is. It is not like the world one would expect to have been created by a powerful, benevolent being. The evidence seems completely contrary. For every person god supposedly helps, dozens of people are left to die by way of disease, violence, starvation, and other unimaginably terrible deaths.

I have been told over and over that god allows evil in the world for free will's sake. However, this explanation seems weak to me. If god is so powerful, he might come up with some other way. I don't think the "best of all possible worlds," as Leibniz concluded the world must be if created by a benevolent god, is one where the prayers of a kid looking for his teddy bear or a woman for her car to start so she can make it to work are answered even as innocent children burn or starve to death elsewhere. If god exists and is well-meaning, he really, really needs to rethink his priorities.

I've read many times that it takes more faith to be atheist than theist. While I admit that someone who believes that there is no god and could never be convinced otherwise is probably dogmatically clinging to faith of a kind, I don't think that that's how it is for me. Presented with the right evidence, I would believe in god. But it seems more likely than not that there is no personal god, to me, because the world I find myself in is inconsistent with that idea. So how am I clinging to faith more than a theist, if I interpret things in the most realistic way possible while being prepared to change my beliefs based on new data?

I'm sure there are those who would accuse me of not giving god a chance. This is bull. I served a full-time mission working every waking hour, seven days a week, for two years. I rode a bike through the hail and in 110 degree 90% humidity, being rejected from dawn to dusk in a language I had to learn as I went. I have always given 1/10 of my income to the church. I have spent my life saying constant daily prayers, reading the scriptures, participating in church service, and forever ignoring any doubts that came my way.

I would say that 20+ years seems long enough. If god were going to throw me a bone, I'd think maybe he would have done it by this time. After all, I've probably lived more than a quarter of my life, and some of my most important decision-making years at that, in his service.

Even if there turned out to be a god who was even slightly interested in human affairs and the lives of individuals, I very much doubt that I was raised in his correct religion. What are the odds? Not good. Ignoring the church's inconsistencies in teachings throughout the last couple of centuries, it occurs to me that maybe god would do a better job promoting the church that he supposedly endorses.

Maybe there is some kind of "first cause" or "creator" of the universe, but there is nothing to indicate this thing's characteristics. Even its sentience is a completely baseless assumption. This "god" could very well regard the universe as a toy, maybe it hasn't even noticed humanity in all of the vastness of space. Or maybe it has, is malevolent, and brings suffering into the world for its own pleasure. So the entire basis of a rational path to theism is groundless... if you have been personally convinced of god's existence, fine, but you can't use that to convince me, your conversion experience is not even consistent with the conversions of others!

Now I'm ranting, so I'd better stop. But people say some dumb things about the way I think, and sometimes it irks me.

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Making Watches with Faith

I heard a story fairly recently about two sister missionaries. They were driving out in the middle of nowhere when their car ran out of gas. Not immediately knowing what to do, they consulted. It occurred to one of them that they had some drinking water in bottles in the car. Why don't they pray that the water be turned to gasoline, and pour it into the gas tank? They fervently prayed, and emptied the bottles into the fuel port. Full of faith, they entered the car and attempted to start it. The water was pulled into the engine, where it caused ruinous damage. The car, needless to say, did not run.

Everyone laughed at the silly sisters. Then I said, to test them, "we all know that prayers for real things don't get answered. Only imaginary things." The group awkwardly ignored my statement, a little shocked at the suggestion. But isn't this the case? Pray for help on your test, and you suddenly remember something you had studied. Pray for comfort on a hard day, and a friend comes calling. See? Prayer works! But pray for something that probably would not have happened anyway... you silly person! That's absurd!

It is postulated that prayers are only answered when they are in accordance with the will of god. But why would he make his will dependent on prayers of antlike mortals?

"Okay, this is what I want to do. But I won't do it unless someone prays for it. Okay... so now how do I do this? Maybe prompt someone to pray for it? *prompt prompt* It worked!"

So god does things only after he gets someone to ask for it. Doesn't he have better things to do? That's the same as your friend who says "I had a crazy dream last night." and looks up at you hopefully, and then further prompts "Man, it was such a crazy dream!" and again pauses. You throw up your hands and say "I've been listening! If you want to tell the dream just do it already!"

On an entirely unrelated note. I despise the Watchmaker Argument. It goes like this:

You walk up a tall, remote mountain and find a beautiful gold watch, still running, on the ground.

Do you assume that it formed there spontaneously? No! You just know someone made it!

The [universe/humans/earth/etc] is the same way! You can't tell me someone made it, it's too complex!

Okay, may I please point out how this is a ridiculous straw-man? Put down with a little less sugary rhetoric:

1. Object X exists.

2. Object X is complex.

3. There exists at least one intelligent being who makes object X.

4. It is very unlikely that object X could exist spontaneously. (from 2)

5. Object X was most likely made by an intelligent being. (from 4,3)

6. An intelligent creator of object X most likely exists. (from 1,5)

Lovely, isn't it. But wait? Looking at the steps of this proof, we notice that one of the assumptions (step 3) is exactly the same as the conclusion (step 6), which depends on step 3!

This is what we call FREAKING CIRCULAR!

I'll throw in an extra two bits for good measure. This argument implies that the existence of a watch spontaneously by chance is unlikely because of its complexity and perfection. Same with us, right? But wait, isn't god the most ultimately perfect and complex being in existence? Hmm. So while it is unlikely that the watch would exist spontaneously, it is less likely that a creator of watches spontaneously exists! And it is further unlikely that someone who could design and build the creator would exist spontaneously, without being made. So if you're going to appeal to probability, you'd better know that while yes, the spontaneous existence of intelligent life like ours is unlikely, you are not getting better odds by assuming a creator.

Everyone laughed at the silly sisters. Then I said, to test them, "we all know that prayers for real things don't get answered. Only imaginary things." The group awkwardly ignored my statement, a little shocked at the suggestion. But isn't this the case? Pray for help on your test, and you suddenly remember something you had studied. Pray for comfort on a hard day, and a friend comes calling. See? Prayer works! But pray for something that probably would not have happened anyway... you silly person! That's absurd!

It is postulated that prayers are only answered when they are in accordance with the will of god. But why would he make his will dependent on prayers of antlike mortals?

"Okay, this is what I want to do. But I won't do it unless someone prays for it. Okay... so now how do I do this? Maybe prompt someone to pray for it? *prompt prompt* It worked!"

So god does things only after he gets someone to ask for it. Doesn't he have better things to do? That's the same as your friend who says "I had a crazy dream last night." and looks up at you hopefully, and then further prompts "Man, it was such a crazy dream!" and again pauses. You throw up your hands and say "I've been listening! If you want to tell the dream just do it already!"

On an entirely unrelated note. I despise the Watchmaker Argument. It goes like this:

You walk up a tall, remote mountain and find a beautiful gold watch, still running, on the ground.

Do you assume that it formed there spontaneously? No! You just know someone made it!

The [universe/humans/earth/etc]

Okay, may I please point out how this is a ridiculous straw-man? Put down with a little less sugary rhetoric:

1. Object X exists.

2. Object X is complex.

3. There exists at least one intelligent being who makes object X.

4. It is very unlikely that object X could exist spontaneously. (from 2)

5. Object X was most likely made by an intelligent being. (from 4,3)

6. An intelligent creator of object X most likely exists. (from 1,5)

Lovely, isn't it. But wait? Looking at the steps of this proof, we notice that one of the assumptions (step 3) is exactly the same as the conclusion (step 6), which depends on step 3!

This is what we call FREAKING CIRCULAR!

I'll throw in an extra two bits for good measure. This argument implies that the existence of a watch spontaneously by chance is unlikely because of its complexity and perfection. Same with us, right? But wait, isn't god the most ultimately perfect and complex being in existence? Hmm. So while it is unlikely that the watch would exist spontaneously, it is less likely that a creator of watches spontaneously exists! And it is further unlikely that someone who could design and build the creator would exist spontaneously, without being made. So if you're going to appeal to probability, you'd better know that while yes, the spontaneous existence of intelligent life like ours is unlikely, you are not getting better odds by assuming a creator.

Monday, November 1, 2010

Epiphany

I was just noticing that I have never felt something so close to conviction, fervor, and zeal as I have recently. I always had an uneasiness in the back of my mind when participating in and even promoting the church my parents raised me in. Vague awareness of the cognitive dissonance. But now, I feel so liberated. It just feels right to admit to myself that I think that this religion is false, as all others probably are. Just accepting the fact that I think Joseph Smith was a charlatan is so amazing compared to always pushing back the sinking doubts about his weird stories and dubious character (even back when I avoided anything not published by the LDS church about Smith, regarding it, like a good Mormon, as diseased lies from the devil).

If I were ever to admit this to my parents or church leaders, they would chastise me, I'm sure. I guess I can't blame them, that's what they're supposed to do based on their convictions.

But being at a religious university, surrounded by Mormon professors and Mormon classmates in a predominantly Mormon area, there is no one with which to share this joy I feel in my freedom to think. It's damned lonely.

I thought Satan was supposed to use peer pressure and loneliness to encourage me to apostatize.

If I were ever to admit this to my parents or church leaders, they would chastise me, I'm sure. I guess I can't blame them, that's what they're supposed to do based on their convictions.

But being at a religious university, surrounded by Mormon professors and Mormon classmates in a predominantly Mormon area, there is no one with which to share this joy I feel in my freedom to think. It's damned lonely.

I thought Satan was supposed to use peer pressure and loneliness to encourage me to apostatize.

The Law of Gravity

...The Mormon church seems obsessed with gravity.

The recent talk by Elder Packer that has gained so much attention by way of its blatant homophobia included one of these weird references. In fact, I wasn't even phased, to be honest, by the anti-gay sentiments; it's what I expect. But when he talked about "a law against nature would be possible to enforce," I immediately thought, "That is the worst metaphor I've heard in a while."

What is there to enforce in a law that permits something? And if people want to marry people of the same gender, how is that in any way impossible? The nullification of gravity is impossible (so far as we know), but it seems like the comparison doesn't hold at all when it is held up next to a law allowing people to do something that is completely defined by words and contracts and other arbitrary things.

So, I was reading in Mormon Doctrine the other day (I still read my daily scriptures in case anyone finds out I am a closet atheist, because then they have nothing to berate me with). Elder McConkie states in the section on "Law" that,

Once a law has been ordained, it thereafter operates automatically; that is, whenever there is compliance with its terms and conditions, the promised results accrue. The law of gravitation is an obvious example. Similarly, compliance with the law of faith always brings the gifts of the spirit.

Now, as much as I love this passage solely for the selection of the word "accrue," I couldn't help but notice that the monstrous bad-gravity-metaphor has once again reared its ugly head. Are you telling me that when I comply with the conditions of gravity, the promised results accrue? I didn't even know I had a choice!

Okay, so maybe he was going for something like "if you walk off a cliff, the promised results accrue. *SPLAT*" But it sure doesn't allude to this effect very directly. I would think something like, I don't know, a vending machine or maybe a light switch or something that has an obvious options->choice->results relationship might better convey his meaning. Gravity is pretty much G*m1*m2/r^2, no matter what you decide.

Anyway, I decided to go to lds.org and investigate: are there more of these references to gravity used to attempt to convince us not to sin?

Here is one that wants to convince you that faith is like believing in gravity through experience as a little child. You can't see it, but it's there! Just like the spirit! (Why do people keep using this same silly argument?)

And here we read that, "The law of gravity is an absolute truth. It never varies. Greater laws can overcome lesser ones, but that does not change their undeniable truth." So gravity is a good example of a law that can't be violated, except of course whenever some "greater" law overcomes it. Apparently this "absolute" law is subject to every whim and caprice of god, so what is the point of mentioning it as an example in the first place?

In this one, we are admonished to understand the importance of law. After all, imagine what would happen if the law of gravity were suspended! We would all die! I guess I can't argue with that, although I might point out that in a universe where such suspension occasionally occurred, any intelligent species might likely find itself well-adapted to survive such upsets. Once again, over-extended as an analogy, but this time it at least makes some sense.

Here we read that "Physical laws, such as the law of gravity, never change; but we change our definitions of them as the scientific community learns more about their operation. Spiritual laws also never change, and we orchestrate our lives according to where we are in our understanding of those truths." One might wonder why god chooses to let us sporadically work out the truth on some fronts (like gravity) but insists that whatever is said by religion has always been taught. (Despite the fact that the things said by even a single religion change with great rapidity, resulting in a terribly high incidence of retcon.)

I digress, but again I ask: why the hell use gravity for your metaphor when you have to take such pains to make it fit?

And last but not least, we have an article by Elder Packer written some 18 years ago where he apparently originally used the whole "do you think a vote to repeal the law of gravity would do any good?" My first reaction was that I see, here is a doddering old man who reused a well-written metaphor from years ago, but not so nimbly this time. I was ready to give him this particular benefit of the doubt until I started reading what he wrote in the article. It is just the same thing, trying to use a physical law to justify his declaration of his particular moral beliefs are irrevocable for all eternity. The article even slightly contradicts itself in giving examples of sure, we could pass a law that does this, but we can't make it right. So... we can pass these "laws against nature," as well as enforce them, except that we can never redefine morality? Okay, I guess, but I haven't really been convinced of anything, here. The acceptance of this doctrine is dependent on the reader already accepting eternal, universal, divinely-inspired law of the packerlicious flavor.

So. The law of gravity has been gratuitously co-opted by the Mormons to poorly demonstrate the importance of the particular "god's eternal immutable laws" of the time. One wonders why they leave out the strong and weak nuclear forces, and for that matter the electromagnetic force? There are literally infinite terrible metaphors that can be constructed by appeal to the physical laws, and I see a lot of unexploited territory here, Elder Packer.

The recent talk by Elder Packer that has gained so much attention by way of its blatant homophobia included one of these weird references. In fact, I wasn't even phased, to be honest, by the anti-gay sentiments; it's what I expect. But when he talked about "a law against nature would be possible to enforce," I immediately thought, "That is the worst metaphor I've heard in a while."

What is there to enforce in a law that permits something? And if people want to marry people of the same gender, how is that in any way impossible? The nullification of gravity is impossible (so far as we know), but it seems like the comparison doesn't hold at all when it is held up next to a law allowing people to do something that is completely defined by words and contracts and other arbitrary things.

So, I was reading in Mormon Doctrine the other day (I still read my daily scriptures in case anyone finds out I am a closet atheist, because then they have nothing to berate me with). Elder McConkie states in the section on "Law" that,

Once a law has been ordained, it thereafter operates automatically; that is, whenever there is compliance with its terms and conditions, the promised results accrue. The law of gravitation is an obvious example. Similarly, compliance with the law of faith always brings the gifts of the spirit.

Now, as much as I love this passage solely for the selection of the word "accrue," I couldn't help but notice that the monstrous bad-gravity-metaphor has once again reared its ugly head. Are you telling me that when I comply with the conditions of gravity, the promised results accrue? I didn't even know I had a choice!

Okay, so maybe he was going for something like "if you walk off a cliff, the promised results accrue. *SPLAT*" But it sure doesn't allude to this effect very directly. I would think something like, I don't know, a vending machine or maybe a light switch or something that has an obvious options->choice->results relationship might better convey his meaning. Gravity is pretty much G*m1*m2/r^2, no matter what you decide.

Anyway, I decided to go to lds.org and investigate: are there more of these references to gravity used to attempt to convince us not to sin?

Here is one that wants to convince you that faith is like believing in gravity through experience as a little child. You can't see it, but it's there! Just like the spirit! (Why do people keep using this same silly argument?)

And here we read that, "The law of gravity is an absolute truth. It never varies. Greater laws can overcome lesser ones, but that does not change their undeniable truth." So gravity is a good example of a law that can't be violated, except of course whenever some "greater" law overcomes it. Apparently this "absolute" law is subject to every whim and caprice of god, so what is the point of mentioning it as an example in the first place?

In this one, we are admonished to understand the importance of law. After all, imagine what would happen if the law of gravity were suspended! We would all die! I guess I can't argue with that, although I might point out that in a universe where such suspension occasionally occurred, any intelligent species might likely find itself well-adapted to survive such upsets. Once again, over-extended as an analogy, but this time it at least makes some sense.

Here we read that "Physical laws, such as the law of gravity, never change; but we change our definitions of them as the scientific community learns more about their operation. Spiritual laws also never change, and we orchestrate our lives according to where we are in our understanding of those truths." One might wonder why god chooses to let us sporadically work out the truth on some fronts (like gravity) but insists that whatever is said by religion has always been taught. (Despite the fact that the things said by even a single religion change with great rapidity, resulting in a terribly high incidence of retcon.)

I digress, but again I ask: why the hell use gravity for your metaphor when you have to take such pains to make it fit?

And last but not least, we have an article by Elder Packer written some 18 years ago where he apparently originally used the whole "do you think a vote to repeal the law of gravity would do any good?" My first reaction was that I see, here is a doddering old man who reused a well-written metaphor from years ago, but not so nimbly this time. I was ready to give him this particular benefit of the doubt until I started reading what he wrote in the article. It is just the same thing, trying to use a physical law to justify his declaration of his particular moral beliefs are irrevocable for all eternity. The article even slightly contradicts itself in giving examples of sure, we could pass a law that does this, but we can't make it right. So... we can pass these "laws against nature," as well as enforce them, except that we can never redefine morality? Okay, I guess, but I haven't really been convinced of anything, here. The acceptance of this doctrine is dependent on the reader already accepting eternal, universal, divinely-inspired law of the packerlicious flavor.

So. The law of gravity has been gratuitously co-opted by the Mormons to poorly demonstrate the importance of the particular "god's eternal immutable laws" of the time. One wonders why they leave out the strong and weak nuclear forces, and for that matter the electromagnetic force? There are literally infinite terrible metaphors that can be constructed by appeal to the physical laws, and I see a lot of unexploited territory here, Elder Packer.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Willingness to Believe

A Christian Rock song came on the radio while I was listening today, and it basically just repeated "nothing you can do can make me leave this life" and "nothing you can say will sway my belief."

Now, I respect a lot of religious individuals, and if they feel that their beliefs are true, I have no objection. I don't know everything (or maybe anything, for that matter). Any one of these religions could be true, and if someone could rigorously demonstrate this to me, I would practice that religion!

So, I call myself an atheist, but I'm probably more of an atheist agnostic, because I find it less likely that there is a god than not. But given new data, I would gladly change my stance.

This sentiment that "nothing you can do/say can shake me" seems destructive to me. Not all religious people believe this, by any means. But if you could find Jesus' remains and verify within a small a small margin of error that they were authentic, or maybe demonstrate that the Hare Krishna are absolutely right, some religious individuals would staunchly ignore these facts and declare even more loudly that they believe. This does not seem like a very good way to find the truth.

I imagine there are some of the religiously inclined who would accuse me of being stubborn and failing to investigate the evidence thoroughly. I'm unwilling to try faith, unwilling to believe anything, or something along those lines.

I maintain a belief that maybe one of the many religions in the world is true, but I doubt it because I have never been able to find any convincing evidence for any of them. I am willing to believe, but I can't practically be expected to try out every religion. If god guides me to a correct religion, I'll join up!

Seems to me the most unwilling to believe anything are the most staunchly religious. There are millions of things I would be willing to believe if presented with convincing data that these people would reject without consideration.

So. I respect the religious. They may even be right. But I am a little peeved when I'm dismissed as closed-minded and unwilling to believe things. My flirtations with nihilism have proved to be absolutely pointless and fruitless, so I'm going to take a more existential, pragmatic approach to truth and rely on my experiences.

Now, I respect a lot of religious individuals, and if they feel that their beliefs are true, I have no objection. I don't know everything (or maybe anything, for that matter). Any one of these religions could be true, and if someone could rigorously demonstrate this to me, I would practice that religion!

So, I call myself an atheist, but I'm probably more of an atheist agnostic, because I find it less likely that there is a god than not. But given new data, I would gladly change my stance.

This sentiment that "nothing you can do/say can shake me" seems destructive to me. Not all religious people believe this, by any means. But if you could find Jesus' remains and verify within a small a small margin of error that they were authentic, or maybe demonstrate that the Hare Krishna are absolutely right, some religious individuals would staunchly ignore these facts and declare even more loudly that they believe. This does not seem like a very good way to find the truth.